Back in 2009, Manhattan sat on the edge of its collective metro seat as the new automated L trains rolled out. It wasn’t the first time, though.

New York City, the 20th-century player-coach for America’s subway systems, had rolled out an automated train system long before 2009. In fact, before New York subway cars even had climate controls, they had automated trains.

It was way back in 1962, on January 4. The circuitry was not as sophisticated or microscopic as 2018 or even 2009 for that matter, but it worked. At that time, the unions worried about workers losing their jobs, and rightfully so.

Automation will take all of our jobs in short order, train operators, cabbies, and bloggers. People knew it way back then, but back to the trains…

New York demonstrated that day that an automated line was possible, even with their archaic technology. What they learned influenced other metro systems, but wouldn’t come back to the city for five decades. It was the raddest thing to happen to subways at the time.

New York Subway History

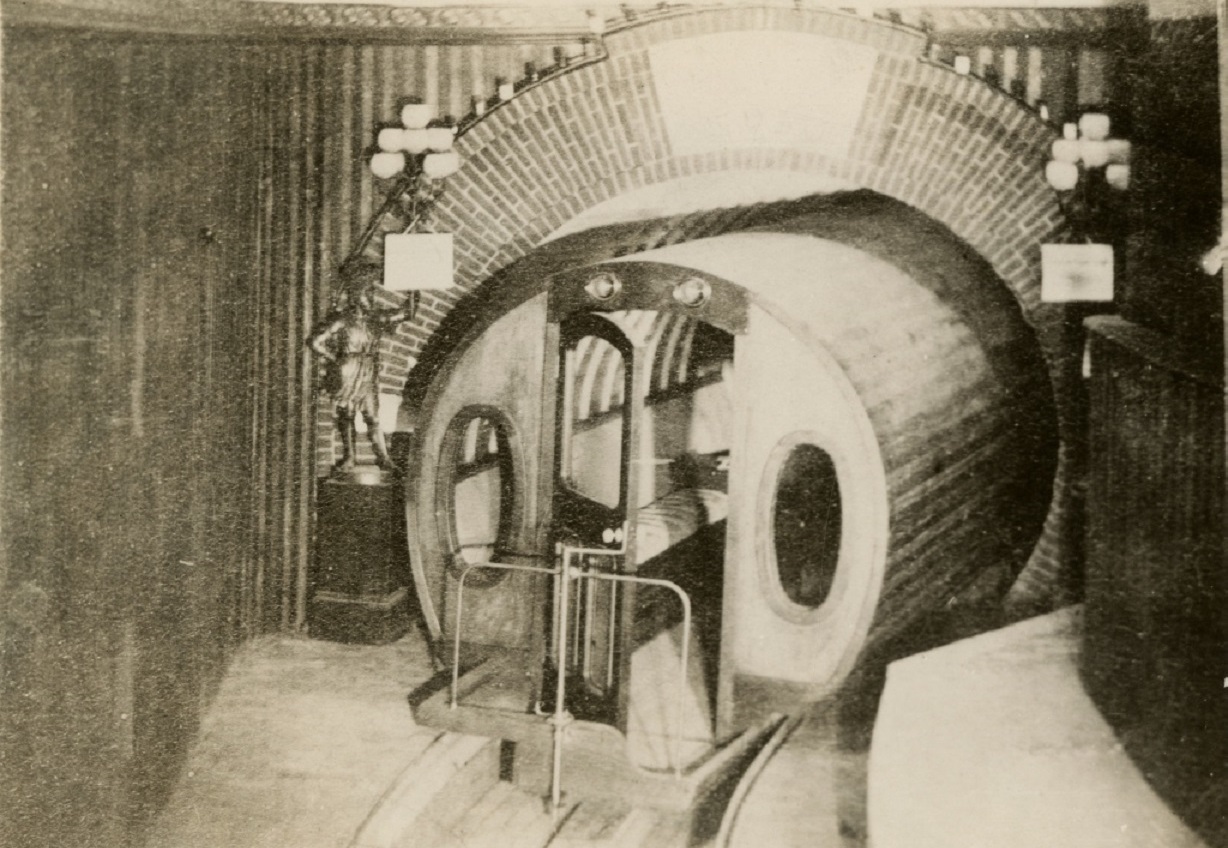

Beach Pneumatic | boweryboyshistory.com

Over 100 years ago, in 1900, New York began construction on the first subway lines, which would eventually spawn their modern system. Those weren’t the very first subway lines in New York, though.

The first one, which failed by the way, was Ely Beach’s pneumatic line way back in 1870. It ran on pressurized air. Beach’s line didn’t take off as a form of transit, but it did become the model for pneumatic mail systems in the city.

Subways as New Yorkers know them today first opened in 1904. As they expanded those early lines in 1912, workers stumbled into Beach’s old line, long since sealed and buried from in a fire at the surface. Beach’s lines are gone now, swallowed up by the construction of City Hall Station on the same plot under Broadway.

In the beginning, there were three line operators, two private, and one owned by the city. By 1940, the city had purchased the two private lines, and by 1953 they formed the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) to manage it all.

This was all preceded in 1934 by the formation of one of the most influential labor unions in the U.S., the Transportation Workers Union of America Local 100.

It deserves mentioning, lest the union reads like the evil antagonists of this story, they weren’t the bad guys. These were good people fighting for their jobs like everyone else.

Automation

1962 Sea Beach Line | bowshrine.com

It was the proposal of Sidney H. Bingham, chairman of the NY Board of Transportation, that they consider an automated line. Initially, the cost seemed too high, but with perseverance, Bingham’s idea gained popularity with the right people.

An initial test on an above ground shuttle that ran down 42nd Street, from Grand Central to Times Square, proved it could work.

By 1959, under the oversight of the new chairman, Charles Patterson, New York was ready to test out this automated system in the subway. They would connect the same two stops, the Times Square and Grand Central, but via subway.

This route, they felt, would least impact the other lines if there were problems. The trains would run on the most state-of-the-art automation, but with an operator at the helm just in case.

What that operator could do in the case of an emergency is up for debate, but the Local 100 insisted on it.

For two years, the automated Sea Beach Line ran, until April 1964. The trains were reliable, but riders complained of rough stops. Some say it was the brakes. Others thought it was the robots.

Despite the fact that many riders skipped manned trains for the novelty of the automated ones, the city shelved the idea after 1964. Union leaders exhaled a collective sigh of relief.

Renewed Interest

By the 1990s, the MTA began implementing more and more automation in the trains. They were not automated completely, but the automatons made the job of the operator easier. It also opened the pathway to the eventual automation or the lines.

What they learned from the 1960s run bore more influence on other systems, like the San Francisco BART line started in 1972, than they did in New York.

When, in 2009, they reintroduced the idea of an automated line, New York again faced pushback from the Local 100. To appease them, as they did in 1962, the trains would run with a babysitter just in case.

The new L trains cost the city $326-million to upgrade, but the expectation was that they will run more efficiently, and more regularly. As we are learning from automated cars, computer-automated transportation runs with fewer errors than humans when we program it right.

In the next decade, New York expects to fully automate all of its trains, but so many of the systems which govern it are already there.

If history is any indication of the future, there will still be an operator sitting at the controls.

Sources: famousdaily.com, roadtrip62.com, nydailynews.com