There were, at one time, many steam-powered car manufacturers, but none would come to symbolize the steam engine more than Stanley Steamer.

The external combustion engine (ECE) or steam engine was not the brainchild of the Stanley twins, but they put the technology on the map. As such, with the demise Stanley Steamer, so too went the ECE.

The Stanley twins oversaw the production Steamers until 1917. The brand lasted until 1926, well into the life of internal combustion engine (ICE) technology.

Steam might have remained alongside gasoline as a fuel source were it not for a number of factors. Specifically, Ransom Olds and Henry Ford could make gas cars a lot cheaper.

The Stanley brothers too, shared as much in the demise of the steam engine as they did its rise. We’ll come back to that…

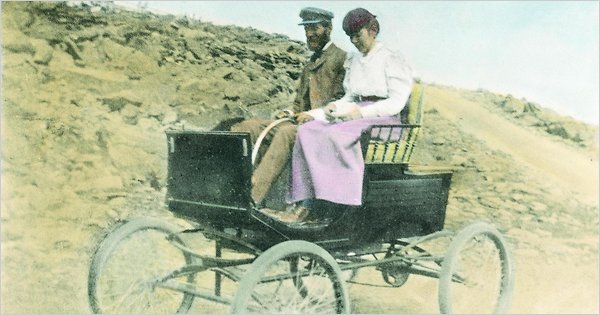

Francis Edgar and Freelan O. Stanley

Born on June 1st, in 1849, in Kingfield, Maine, the twins grew up in an engineering household. Their grandfather taught the boys how to craft violins by age 10.

After the boys finished school, they both did some teaching, but Francis took up photography shortly after that, Freelan made mechanical drawing kits.

After the mechanical kit factory burned down, Freelan joined his brother in the photography biz. In 1883, Francis created a new photographic technique called “dry plate processing.”

The twins founded the Stanley Dry Plate company to manufacture and sell Francis’ new technique.

Then, in 1896, the twins witnessed a horseless carriage at the Brockton Fair, in Massachusetts.

Steamer Tech

After that, life moved much faster for the twins. It was only a year later, in 1897, the boys built their first ECE car. Two years later they’d sold 200 of them via the Stanley Motor Carriage Company.

At that time, nobody sold 200 cars a year, putting them at the top of the car game. Eat your heart out, Ransom Olds.

The Stanley twins’ engines generated power via a huge steel drum of water, reinforced with piano wire around the drum, which would steam when heated from below. That steam, routed to the engine, would power the rear axle with impressive torque for short periods of time.

In an ECE, the combustion took place before the engine, not in it. The dangerous part, other than the possibility of the steel drum exploding, was the open flame heating it from below.

In this case, it was a gas flame.

As far as exploding steel drums went, the Stanleys never suffered one, part of the reason they were successful. Folks saw steam as an older, more-reliable technology, less volatile than one of those “exploding engines” (ICEs).

Performance Legacy

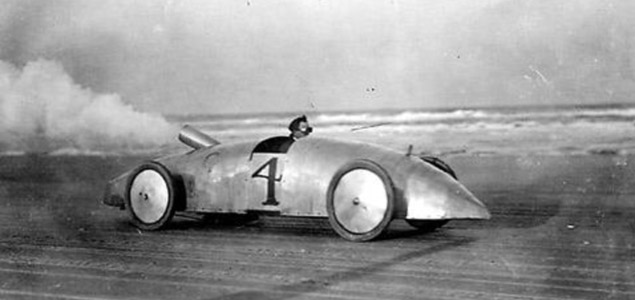

Stanley Racer | lab.cccb.org

Some Stanley Steamers could go over 75 mph for short bursts. For this reason, the twins quickly engaged in racing their cars.

They leveraged clever engineering techniques like using the exhaust steam to preheat the water and superheating the steam before it hit the engine.

The first record they set was in 1898. Francis drove 27.4 mph without a breakdown in front of a 5,000 spectator crowd. This put them on the map.

Then, on August 31, 1899, they set another record by being the first to climb Mount Washington in a horseless carriage. After that, they continued to break speed records well into the new century.

In 1906, a Stanley Steamer made it up to 127 mph. A year later, another went 150 before crashing in Daytona Beach.

To control quality, the brothers insisted they produce no more than 1,000 cars a year, a limitation that would later hurt them as others out-produced them.

With the advent of brands like Olds and Ford, owned by industrialist tycoons, the Steamers could only leverage those performance points so long. Gasoline ICE engines started to beat the records set by steam in every way.

By the end of the brand, the Stanley name landed on around 16,000 vehicles.

On July 13, 1918, Francis died in a car accident trying to avoid farm wagons. Freelan lived until October 2, 1940. He lived long enough to see the Stanley brand fade into obscurity, buried by the production quantity and cost savings afforded by new industrialists.

But, for a few years, the future was steam.

Sources: wired.com, stanleymotorcarriage.com, carhistory4u.com