In the mid-19th century, ships, starting with naval warships, transitioned quickly from wood vessels to metal. It was the dawn of the ironclads, as we call them.

Most anyone who’s stood on the deck of a cruise liner or a port where the ships dock, has wondered, how the heck do they make metal float when cars sink like torpedoes?

Unless we’re talking about this car…

Today’s big metal boats are not the Ironclads of yesterday, heavy and steampunked, but they’re not exactly made from wood either, not the big ones.

How did someone get the bright idea to see if metal would float?

The first Ironclads not only floated, they revolutionized battles at sea and gave birth to what would evolve into our modern method of warship engineering.

The Gloire & The HMS Warrior

The French Gloire | jose.chapalain.free.fr

Credit goes to the French for engineering the first ironclad in 1859, the Gloire. Before that, we had boats that had iron parts, rivets or were even partially shielded.

These engineering elements weren’t enough to withstand the developments in gun technology.

Around the time of the Crimean War, in the 1850s, history records the first explosive shells used in the Navy. These shells were too powerful against wooden vessels. One hit meant could mean the end of a ship

The French’s Gloire and the British response to that technology, the HMS Warrior, would withstand some of that shelling.

In both the Gloire and the Warrior, the iron metal plating covered the vulnerable parts of the ship. They were not yet dealing with submarine strikes, so the lower hull was still wood.

On the Warrior, the ends of the ship remained unprotected, assuming any serious hits would come from the side.

By 1862, there were 16 ironclads in use or under construction between the French and British. The revolution was upon us.

The American Civil War

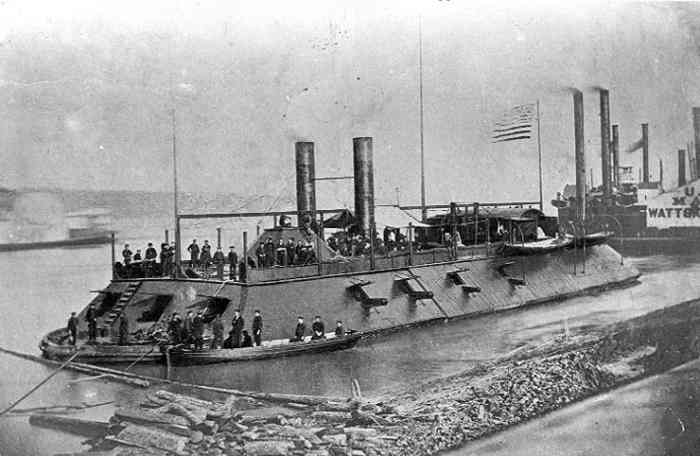

1st Generation Ironclads looked weird. This is the USS Essex. | steamboattimes.com

In the United States, there were two types of ironclads, Union, and Confederate. When the war started, both sides were all wood.

The Confederates went for it first. After all, the Union claimed most of the pre-existing U.S. Navy.

Like the HMS Warrior, the Confederate ironclads they built by converting wooden ships, old steamers, adding iron-cladding to cover the above-water parts. They looked like the USS Essex in the photo above. The Confederates enjoyed the success of being first to build one, but that party wouldn’t last.

The Confederates enjoyed the success of being first to build one, but that party wouldn’t last.

The Union, leveraging their intelligence network, learned of the South’s plans and got to work on a few of their own, but not fast enough. The Confederate Navy sank several Union ships before the Union introduced the USS Monitor in 1862, their first worthy ironclad.

That ship was a keel-up design, revolutionary in every way. It housed some forty innovations never before seen on a boat.

CSS Virginia vs. USS Monitor | skipjackmarinegallery.com

The first meeting of ironclads, the CSS Virginia vs. the USS Monitor ended in what history records as a draw, even though the Monitor pulled out first. Both sides needed new naval strategies.

The response from the Union was to build more ironclads, fifty of them. This was not only the first massive overhaul of a navy but what started the United States down the path as the most advanced naval force in the world.

We all know how that war ended. It wasn’t the ironclads that affected the war so much as how the war drove the development of ironclads and defensive tech. We would borrow what we learned on the water with land vehicles, tanks, and armored cars.

By 1864, the world was over wood warships.

The Move To Armored Metal

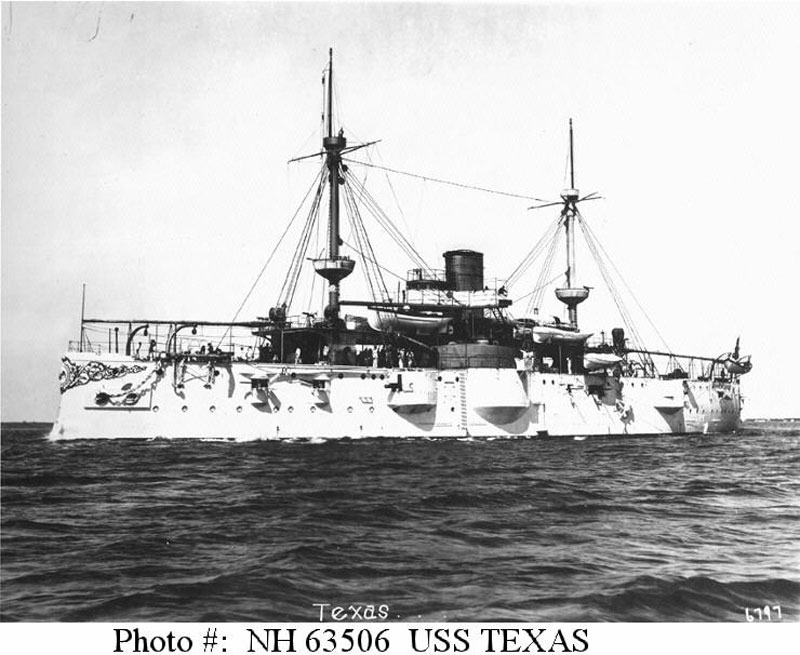

The 1st US pre-dreadnought, The USS Texas. Note the figurehead on the bow. | en.wikipedia.org

We used ironclads up until World War I, but by then we were replacing them with pre-dreadnoughts and dreadnoughts. The first pre-dreadnoughts came about in the late 19th century.

In many ways, their hulls started to resemble what we see today in shipbuilding. Gone were the layers of iron on top of hardwoods.

Engineers built these ships from steel, hardened like armor. They combined the otherwise soft steel with wrought iron, which allowed them to use the pieces as all the structural parts, simplifying the design of the boats.

The pre-dreadnoughts were metal riveted to metal. They way they assembled these ships would inform the construction of passenger ships, like the RMS Titanic, and the cruise ship lineage that followed.

We still make boats out of wood, but nothing for war. The only wood boats we now make are either a novelty reconstructions, like a tribute boat. Otherwise wood makes up the frame of a fiberglass hull for a recreational craft.

What remains to be seen is what will replace the armored ship hulls we’ve come to trust? Will a material like a graphene materialize into ship designs or maybe something else?

Like it or not, someday, what we build today will look like heavy, antiquated museum fodder.

Source: americancivilwarstory.com