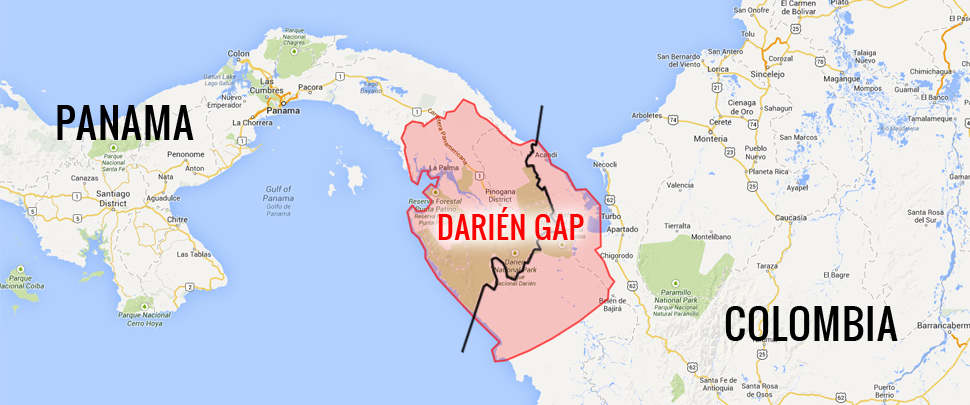

While it’s true that the Pan-American Highway goes from Alaska to the southern tip of Argentina, there is a long section over Panama into Colombia which remains unpaved. It’s the Darién Gap.

The likelihood of a road through there is improbable at this point. The likelihood of that improbability stopping determined adventurers from crossing the Gap are also improbable.

The Darién Gap crosses 10,000 square miles of untamed jungle. It’s wet to the point of swampy in areas. Where it’s not too wet to drive, guerrilla groups operate in the jungle.

Vehicles get stuck. People disappear. It’s a wonder anybody bothers. The Darién Gap should be what keeps wanderers from trying to cross Pan-America, but for some, it’s the very reason to try.

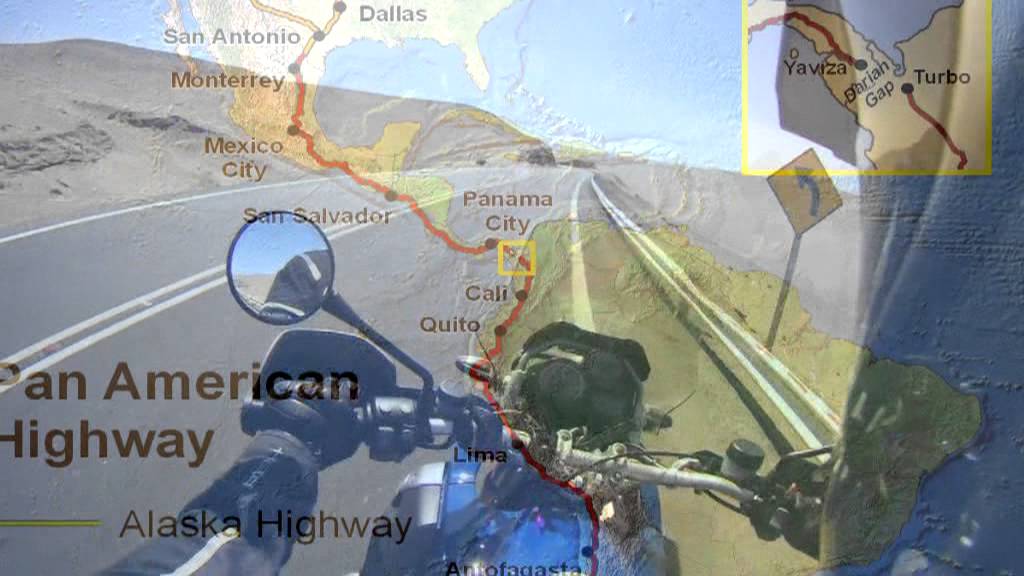

Pan-American Highway

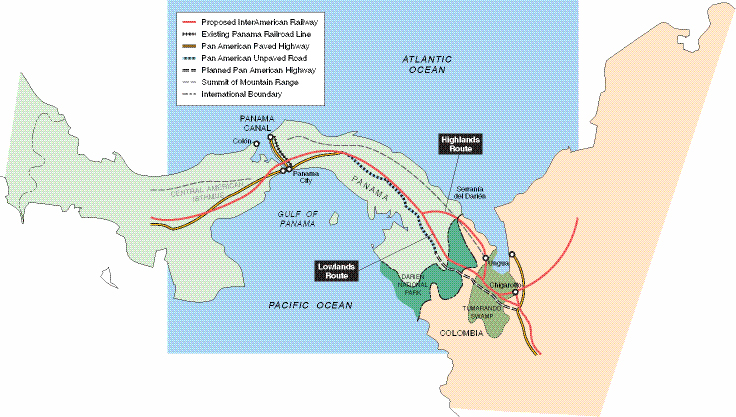

The first concept of a Pan-American crossing was a railway, but the rise of the automobile redirected that conversation.

By 1925, 13 nations in the Americas signed the Convention on the Pan-American Highway (PAH). Mexico finished their section first in 1950.

The rest of the PAH completed in the following two decades, but the Americans, and in this case we mean all of them, hit a snag in the ’70s. That snag was the Darién Gap.

At the south end of Panama, the Earth became too murky to pave by conventional means.

Plans

In 1971, the United States took the helm of closing the gap. For a minute, everyone sighed in relief. The U.S. could do anything, cross any obstacle. Look what they did with the Panama Canal.

By 1974, the would-be engineers of the gap crossing hung up their drafting pencils. Environmentalists and scientists had been loudly protesting the plan.

The Gap provides a barrier between the Southern American countries and the North. It is a diverse ecological land, one that’s hard for even animals to cross.

Consequently, viruses spread my cattle haven’t been able to cross into Central America or Northern America. The oft-cited example is foot-and-mouth disease, something animal farmers north of Panama are happy not to fight.

Solutions

Today, determined adventurers take the Pan-American as far south as they can into Panama, then cut east to the ocean. There, they can catch a boat to Colombia, meeting back up with the Pan-American Highway south of the Gap.

The other option is to attempt an off-road crossing through the jungle. A handful of people have made it, some on motorbikes, others using specially equipped off-road vehicles.

Crossing the Gap, one must carry not only supplies to survive, including guns, but the means to cross rivers and swamps. Then, one must also be ready to turn around and re-route. It’s slow, thankless work.

Crossers

A Land Rover and Jeep team made it across first in 1960, but they didn’t start at the beginning of the PAH. It also took them five months. Mind you, that was only to cross the Gap.

The first guy to do the whole route, PAH, Gap and all, was a man named Ed Culberson. He rode a BMW R80G/S the whole way, using a private guide to clear the Gap.

In all, fewer teams than this writer has fingers have made it across.

The FARC rebels who once caused hell for the Colombian government and some would-be Gap crossers laid down their arms this summer.

This may mean more people try to cross the Gap in the coming years, but it won’t negate the environmental risks of building bridges there.

That will not happen in this lifetime.