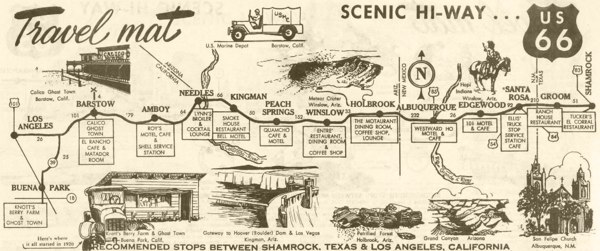

It was the road that connected Chicago with Los Angeles. For many, it was the road to salvation. Once a collection of smaller highways connecting towns, in 1926, Route 66 drew a line to the coast. We didn’t pave it until ’38, but the plan was set in the 20s.

(source: idea-sandbox.com)

If you grew up in the 70’s or later, you knew little of Route 66. By the 80s, we’d decommissioned it. By that time, Route 66 was long since buried under the dust from a sprawling network of interstate freeways.

Still, you would hear about this famous Route in songs and movies, perhaps learning in time that 66 was the mother road to America. It was the first road that people traveled en masse to escape the dust bowl of the 30’s.

You may even have happened upon vintage signage, indicating you were on a piece of America’s Main Street, somewhere in the middle of nowhere, but you’ve always wondered, if it was so great, whatever happened to it?

Despite efforts to retain the mystique of 66, we forgot about it once we could travel without stop signs on multilane raceways. The US freeway systems meant that unless you were crazy nostalgic, driving 66 meant headaches and risk not worth the effort.

That was not always the case, though. When it started, Route 66 broke up the monotony of the railway, it connected towns, but mostly it moved a nation.

Before 66

(source: pinterest.com)

There were roads, some big enough to call highways, sure. They connected towns. For most people, if you wanted to travel west, the train was the way to go.

The train was reliable. It was easy. It was cheap. If the train broke down, it wasn’t your problem to fix. On the train, there were comforts like food, booze and even places to sleep or play games.

The train was smooth travel. Roads were not so smooth. Route 66, in particular, was just dirt in places.

Long stretches of road, which we would one day pave to make 66, were little more than wagon trails along the 35th parallel, a leftover project of the Navy from the 1850’s.

The Heyday

(source: thelostadventure.com)

Compared to the alternatives, Route 66 was an easy ride. At first, it was a mixture of gravel and pavement, but it was the first highway we paved the whole way.

The Route swung south, through some beautiful country, but mostly over flat land. If you have cars, you need gas stations and places to eat. All along 66 businesses flourished. By some accounts, this where the fast food industry made its first stand.

They called the first people who traveled 66, “Oakies,” or “Arkies,” as they came from Oklahoma or Arkansas. By WWII, 66 made a great passageway for moving military equipment. During the 50’s, families used 66 for vacations to Los Angeles.

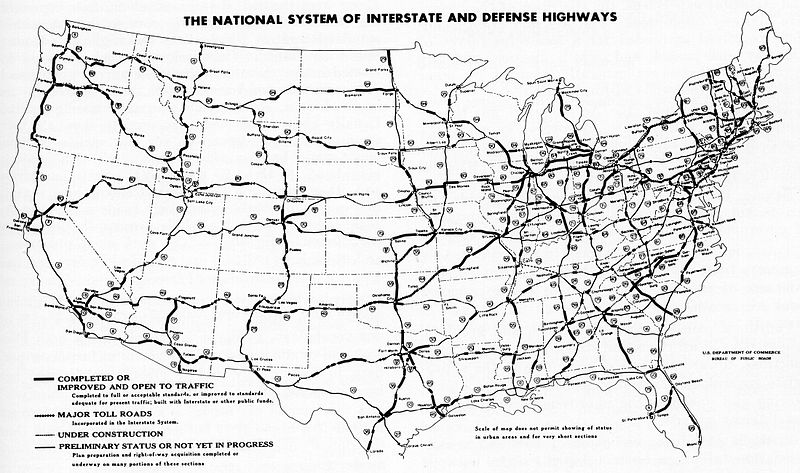

The Interstate Highway Act

(source: blog.wilvaco.com)

It was 1956. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, influenced by the German autobahn, signed the Interstate Highway Act. It was also known as the Federal-Highway Act or the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act.

That’s right; it was a military move. The highway system would allow for easier transport in the name of national security.

This act didn’t immediately erase Route 66, but over time, as we built the network of freeways that people still use today, the crumbling parts of 66 fell away.

With the construction of the Turner Turnpike, from Tulsa to Oklahoma City, the first bypass of 66 took form. That highway ran parallel to 66 for 88 miles.

Today

(source: aaroads.com)

There are freeways in use in Illinois and California, the two ends of 66, which commuters still use today. Of course, they look nothing like the old Mother Road.

The Pasadena Freeway in Los Angeles was once part of 66. Veteran’s Parkway in Illinois travels that end of the Route.

We’ve converted sections of 66 into many passageways, some of which you can’t even drive anymore. They are either too rough or designated for non-motor traffic, like bike lanes.

Preservationists have designated sections of the road as historic. Other have attempted to restore the road to its old glory. It’s not likely to happen, mostly because of development since then but also because the cost to restore it wouldn’t make sense.

(source: flickr.com)

Route 66 will fade in time, just as the actual road has faded. This is the fate of all things. Nothing lasts forever.

By the time the generation of kids from the 70’s is old enough to retire, folks will likely not talk about it unless they live near a preserved section.

It will be a passage only historians talk about, people who surf sites that talk about forgotten history, sites like History Garage.