If it weren’t for the pesky jungle, the Pan-American Highway (PAH) would wear the crown for the longest road in the world. What is wears is more of a consolation prize. Guinness Book of World Records counts the PAH as the longest motor-able road.

The problem is that the Derién Gap prevents one from crossing into South America from Panama.

The Auto-Estrada Panamericana, as one calls it in Spanish, travels from the tip of Alaska to the tip of Argentina. Traveling this road is a bucket list item for many adventurers, full of peril, but worth invaluable rewards.

It only took a century to make it what it is today: incomplete.

Pan-American Conference 1889

(source: telesurtv.net)

The idea of the PAH began as a railway concept. Nothing came of the first proposal.

By 1923 when the 5th International Conference of American States convened, cars were more prevalent. Ford had been making Tin Lizzies for over a decade. Roadways were the future.

The United States was already cozying up to the idea of Route 66, which we would commission in 1926. It was probably because, in 1925, 13 nations across the Americas signed the Convention on the Pan-American Highway.

The original plan was a speed construction, but the final product would take nearly 100 years to complete.

North American Challenges

(source: cyclingboardgames.net)

For the record, Mexico wins. They were the first Latin American country to complete their commitment to the Convention of ’25. Of North American countries, they were the first and still the only country to pave roads that count as the official route.

As soon as the PAH reaches the United States, there’s a problem. We have a ton of good highways, too many. We’ve designated none of them as official routes.

Because of this, the route after Mexico splits into two unofficial routes, which don’t converge until Canada, south of the Alaska Highway. That highway takes the route the rest of the way, but it’s still not official.

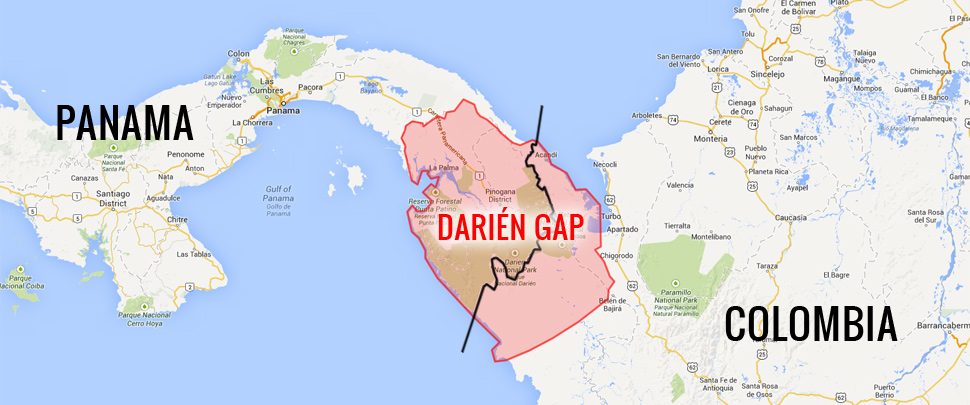

The Derién Gap

(source: spokeandwords.com)

Close the Derién Gap and you get a long official route. Until that point, the CA-1, as they call the PAH in Central America (way to coordinate, CA!) is complete.

It’s not always a great highway, sometimes one-lane each way, but it connects. Then you get to the rainforest marsh. It’s a dense sloppy mess, expensive to cross.

Not only is a matter of the cost, but it is protected lands. Environmentalists would lose their minds, as should we all if construction crews started ripping through there. The damage to not the land, but one of the planet’s most valuable ecosystems, and therefore the damage to Earth would be immense.

On top of that, there are native people in that area who would also suffer the development of a road. Some have proposed ferries and bridges, while some adventurers try to cross it on bikes or foot without help. It’s a dangerous proposition. People disappear in the gap.

BTW: Did anyone ask Elon Musk? Let him tunnel the PAH under that forest. Problem solved.

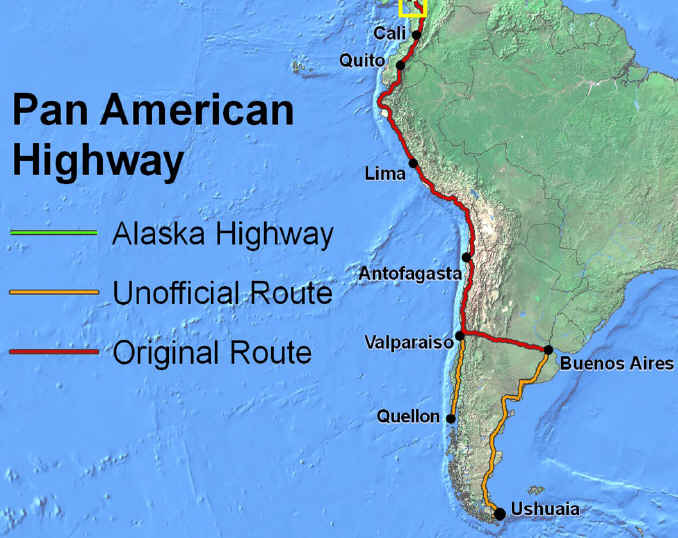

The Southern Tip

(source: cyclingboardgames.net)

We pick the PAH up in Columbia, where it travels uninterrupted through Ecuador, Peru, and Chile. At Santiago Chile, the official route cuts east to the shores of Buenos Aires, Argentina, then south to the cape, but that southern piece is not the official route.

(source: drivetheamericas.com)

Why can we not consider the unofficial section of the PAH as official, who knows? It seems like after 100 years, at least the United States could get it together.

As is the case with large projects, there are many interested parties. Once a part of the road become the official route, the unofficial route goes away.

Just ask Brazil and the other countries of the north-eastern part of South America. They want a piece of the action too, but you won’t see their unofficial roads on any map of the PAH.

Still, what a route!