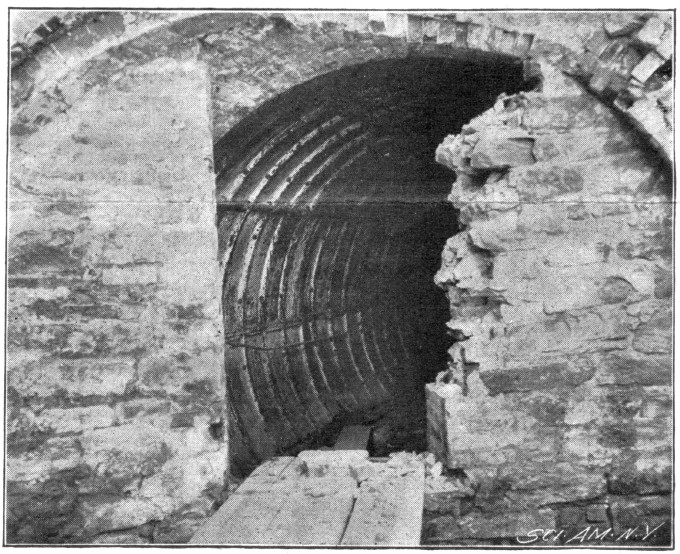

When the demo crew for Manhattan’s BMT Broadway Line broke into the old Beach tunnel, they found the remains of New York’s first subway car. They also found the tunneling shield used to carve out the first line and a piano which once filled the old platform with music.

1912 | nycgo.com

If you stand on the City Hall station under Broadway, you can say you’ve stood where history first tried to put trains underground.

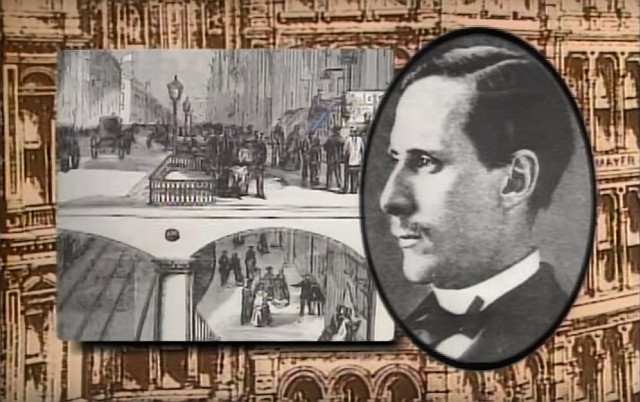

The man behind the first train, Alfred Ely Beach, was a man of many incomes, enough to fund projects like an underground rail.

He imagined a future where New Yorker’s could slide comfortably below the chaos on the streets, like some kind of steampunk science fiction, in large mail tubes.

What came of his idea was just that, a system for moving mail.

Alfred Ely Beach

The boy who became the man started life in Springfield, Massachusetts. His father was a successful publisher, a fact that would influence Beach’s life.

When he finally stopped working for Daddy, he and a friend, Orson Munn, bought a little periodical called Scientific American. At the time, it was yet a nascent publication.

Beach and Munn would run the magazine until they died, passing it on to their respective bloodlines for generations. They enjoyed other successes along the way, including a patent agency, from which they both launched inventions.

One of their inventions was a typewriter for the blind. That was Beach’s idea. So was the school for freed slaves that he founded, the Beach Institute.

If he were to have stopped there, he would have lived a more exciting and contributing life than most people could dream. Sometime after 1863, while stuck in New York’s worst traffic, Broadway, he hatched an idea…

The Plan

Beach had already conceived of using pneumatic tubes for moving mail and packages across town. Scaling that idea into a pneumatic rail was only logical.

The idea of an underground rail was nothing new. London had the Metropolitan Railway and New York visionaries already talked about building an underground rail in Manhattan, especially under Broadway.

They had been thinking steam locomotion, though, not pneumatics.

In 1867, Beach demoed his idea at the American Institute Exhibition in New York. By 1869 he was tunneling under Broadway, but first, he had to game the system a little.

Beach ran into opposition from a New York politician, William Tweed, who did not support his project. Tweed controlled the influence of much of New York’s patrons, so without his support, Beach had to put up his own money, $350,000.

As a side to the story, William Tweed would later go to jail for embezzlement in the tens of millions, possibly [read: probably] more. Funny how that always happens.

But, back to Mr. Beach…

To build his tunnel, Beach had to tell a little white lie. After he received approval for his permit to build mail tubes, he amended the permit to build a large tube to house many small tubes.

Once he had that amendment approved, he could push forward with his pneumatic line, A.K.A., the real plan.

The Beach Pneumatic Line

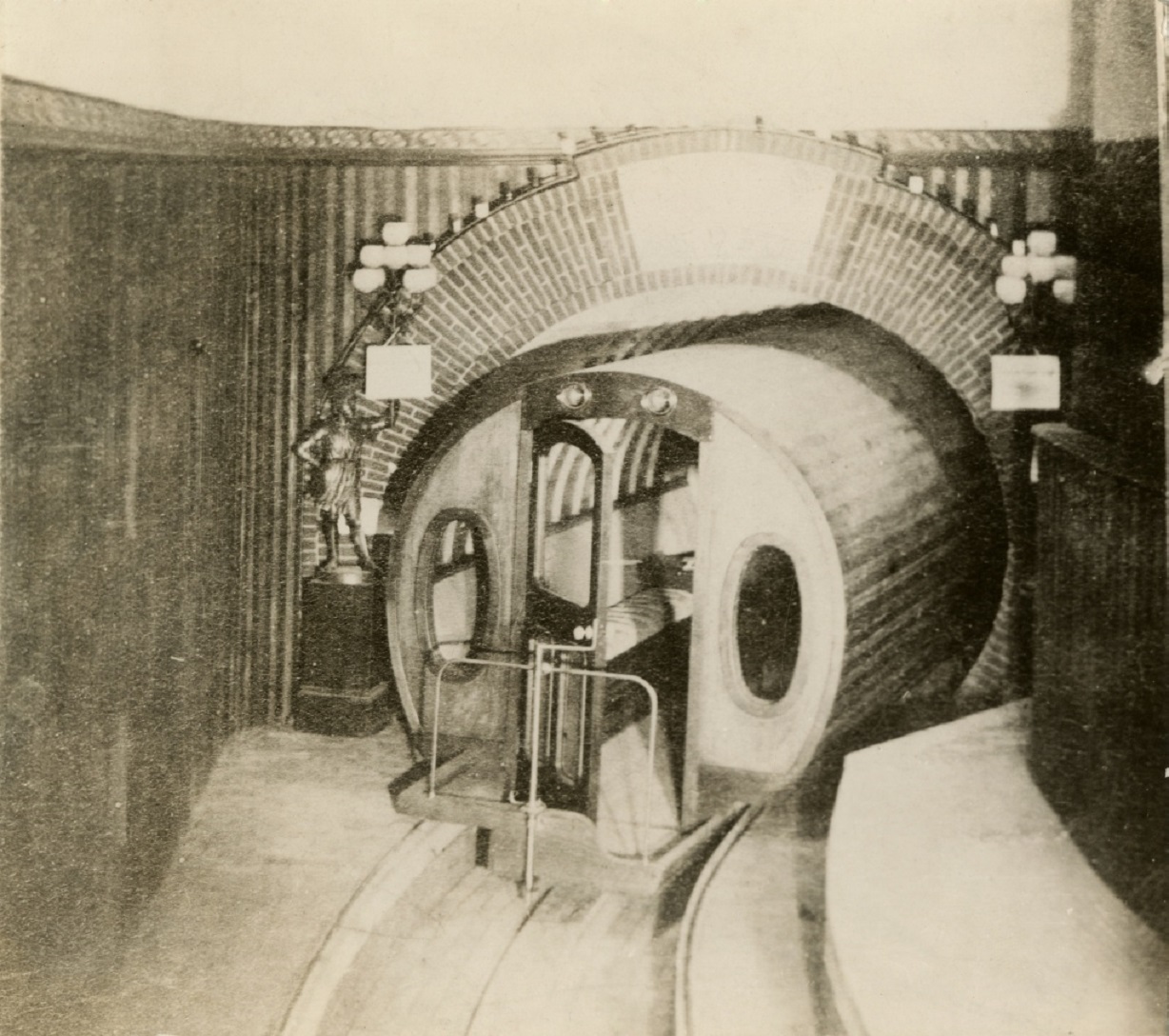

On February 26th, 1870, the first New York subway whooshed below Broadway, moved by pressured air. There were no cables, steam engines or noisy cars. It was one car inside a pneumatic tube.

Rides were 25 cents per person. It drew crowds, 11,000 the first two weeks, but the little corridor did little to get people anywhere.

The plan was to extend the line by five miles, but at first, it only went one block. Riders hopped on out of curiosity, taking it one block, then back again like an amusement ride.

Beach funneled the money to charity, hoping to leverage the publicity to extend his idea. He envisioned ornate stations, large paintings, and luxurious furnishings in his subway, fish ponds and statues.

Within three years the stock market crashed, ridership declined, and he had to close the line. In 1898, the building above the line burned, burying what was underground until the 1912 subway construction.

1912 | readingthroughhistory.com

Beach’s idea wasn’t for naught. It gave birth to the New York pneumatic mail system, sprung from the original permit submitted by Beach. New York used that system until the 1950s.

Some say you can still access part of the old Beach line via a manhole near Broadway, but good luck finding it.

The tale begs the question, though. Why didn’t we build pneumatic railways instead of electrical? To the chagrin of futurists everywhere, it was likely a matter of the old boring answer: cost.